Since January 1, 1873, Japan has used the Gregorian calendar, with local names for the months and mostly fixed holidays. Before 1873, a lunisolar calendar was in use, which was adapted from the Chinese calendar.[1] Japanese eras are still in use.

Years

Three different systems for counting years have been used in Japan since following the gregorian calendar.

- The western Anno Domini (Common Era) (西暦, seireki) designation

- The Japanese era name (年号, nengō) based on the reign of the current emperor, the year 2009 being Heisei 21

- The imperial year (皇紀, kōki) based on the mythical founding of Japan by Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

Of these three, the first two are still in current use; Japan-Guide.com provides a convenient converter between the two. The imperial calendar was used from 1873 to the end of World War II.

Months

Names for the modern Japanese months literally translate to "first month", "second month", and so on, combined with the suffix -gatsu (month).

- January (ichigatsu)

- February (nigatsu)

- March (sangatsu)

- April (shigatsu)

- May (gogatsu)

- June (rokugatsu)

- July (shichigatsu)

- August (hachigatsu)

- September (kugatsu)

- October (jūgatsu)

- November (jūichigatsu)

- December (jūnigatsu)

Traditional Names

In addition, every month has a traditional name, still used by some in fields such as poetry; of the twelve, shiwasu is still widely used today. The opening paragraph of a letter or the greeting in a speech might borrow one of these names to convey a sense of the season. Some, such as yayoi and satsuki, do double duty as given names (for women). These month names also appear from time to time on jidaigeki, contemporary television shows and movies set in the Edo period or earlier.

The name of month: (pronunciation, literal meaning) (Note: the old Japanese calendar was an adjusted lunar calendar based on the Chinese calendar, and the year - and with it the months - started anywhere from about 3 to 7 weeks later than the modern year, so it is not really appropriate to equate the first month with January.)

| lunar month | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 睦月 | mutsuki, affection month |

| 2 | 如月 or 衣更着 | kisaragi or kinusaragi, changing clothes |

| 3 | 弥生 | yayoi, new life; the beginning of spring |

| 4 | 卯月 | uzuki, u-no-hana month; the u-no-hana is a flower, genus Deutzia |

| 5 | 皐月 or 早月 or 五月 | satsuki, fast month |

| 6 | 水無月 | minatsuki or minazuki, month of water |

| 7 | 文月 | fumizuki, book month |

| 8 | 葉月 | hazuki, leaf month |

| 9 | 長月 | nagatsuki, long month |

| 10 | 神無月 | kaminazuki or kannazuki, "month without gods |

| 11 | 霜月 | shimotsuki, frost month |

| 12 | 師走 | shiwasu, priests run; |

Month subdivisions

Japan uses a seven-day week, aligned with the Western calendar. The seven day week, with names for the days corresponding directly to those used in Europe, was brought to Japan around AD 800. The system was used for astrological purposes and little else until 1876, shortly after Japan officially adopted the Western calendar. Fukuzawa Yukichi was a key figure in the decision to adopt this system as the source for official names for the days of the week. The names come from the five visible planets, which in turn are named after the five Chinese elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), and from the moon and sun (yin and yang).

| day | element | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | 日曜日 | nichiyōbi | Sun |

| Monday | 月曜日 | getsuyōbi | Moon |

| Tuesday | 火曜日 | kayōbi | Fire (Mars) |

| Wednesday | 水曜日 | suiyōbi | Water (Mercury) |

| Thursday | 木曜日 | mokuyōbi | Wood/Tree (Jupiter) |

| Friday | 金曜日 | kin'yōbi | Metal/Gold (Venus) |

| Saturday | 土曜日 | doyōbi | Earth (Saturn) |

Japan also divides the month roughly into three 10-day periods. Each is called a jun (旬). The first is jōjun (上旬); the second, chūjun (中旬); the last, gejun (下旬). These are frequently used to indicate approximate times, for example, "the temperatures are typical of the jōjun of April"; "a vote on a bill is expected during the gejun of this month."

Days

Each day of the month has a irregularly formed, semi-systematic name

- 一日 - tsuitachi (sometimes ichijitsu)

- 二日 - futsuka

- 三日 - mikka

- 四日 - yokka

- 五日 - itsuka

- 六日 - muika

- 七日 - nanoka

- 八日 - yōka

- 九日 - kokonoka

- 十日 - tōka

- 十一日 - jūichinichi

- 十二日 - jūninichi

- 十三日 - jūsannichi

- 十四日 - jūyokka

- 十五日 - jūgonichi

- 十六日 - jūrokunichi

- 十七日 - jūshichinichi

- 十八日 - jūhachinichi

- 十九日 - jūkunichi

- 二十日 - hatsuka (or nijūnichi)

- 二十一日 - nijūichinichi

- 二十三日 - nijūsannichi

- 二十四日 - nijūyokka

- 二十五日 - nijūgonichi

- 十六日 - nijūrokunichi

- 二十七日 - nijūshichinichi

- 二十八日 - nijūhachinichi

- 二十九日 - nijūkunichi

- 三十日 - sanjūnichi

- 三十一日 - sanjūichinichi

Tsuitachi is a worn-down form of tsukitachi, which means the first of the month. In the traditional calendar, the last day of the month was called 晦日 misoka. Nowadays, the terms for the numbers 28-31 plus nichi are much more common. However, misoka is much used in contracts, etc., specifying that a payment should be made on or by the last day of the month, whatever the number is. The last day of the year is 大晦日 ōmisoka (the big last day), and that term is still in use.

japanese National holidays

- January 1 (元日 ) : New Year's Day, Ganjitsu

- 2nd Monday of January (成人の日) : Coming-of-age Day, Seijin no hi

- February 11 (建国記念の日) : National Foundation Day†, Kenkoku kinen no hi

- March 20 or March 21 (春分の日 ) : Vernal Equinox Day, Shunbun no hi

- April 29 (昭和の日) : Shōwa Day, Shōwa no hi

- May 3 (憲法記念日) : Constitution Memorial Day, Kenpō kinenbi

- May 4 (みどり(緑)の日 ) : Greenery Day, Midori no hi

- May 5 (子供の日) : Children's Day, Kodomo no hi

- 3rd Monday of July (海の日 ) : Marine Day, Umi no hi

- 3rd Monday of September (敬老の日 ) : Respect for the Aged Day, Keirō no hi

- September 23 or September 24 (秋分の日) : Autumnal Equinox Day ,Shūbun no hi

- 2nd Monday of October (体育の日) : Health-Sports Day, Taiiku no hi

- November 3 (文化の日 ) : Culture Day , Bunka no hi

- November 23 (勤労感謝の日 ) : Labour Thanksgiving Day, Kinrō kansha no hi

- December 23 (天皇誕生日 ) : The Emperor's Birthday, Tennō tanjōbi

Seasonal days

Some days have special names to mark the change in seasons. The 24 Sekki (二十四節気 Nijūshi sekki) are days that divide a year in the Lunisolar calendar into twenty four equal sections. Zassetsu (雑節) is a collective term for the seasonal days other than the 24 Sekki. 72 Kō (七十二候 Shichijūni kō) days are made from dividing the 24 Sekki of a year further by three. Some of these names, such as Shunbun, Risshū and Tōji, are still used quite frequently in everyday life in Japan.

24 Sekki

| Risshun (立春) | February 4 | Beginning of spring |

| Usui (雨水) | February 19 | Rain water |

| Keichitsu (啓蟄) | March 5 | awakening of hibernated (insects) |

| Shunbun (春分) | March 20 | Vernal equinox, middle of spring |

| Seimei (清明) | April 5 | Clear and bright |

| Kokuu (穀雨) | April 20 | Grain rain |

| Rikka (立夏) | May 5 | Beginning of summer |

| Shōman (小満) | May 21 | Grain full |

| Bōshu (芒種) | June 6 | Grain in ear |

| Geshi (夏至) | June 21 | Summer solstice, middle of summer |

| Shōsho (小暑) | July 7 | Small heat |

| Taisho (大暑) | July 23 | Large heat |

| Risshū (立秋) | August 7 | Beginning of autumn |

| Shosho (処暑) | August 23 | Limit of heat |

| Hakuro (白露) | September 7 | White dew |

| Shūbun (秋分) | September 23 | Autumnal equinox, middle of autumn |

| Kanro (寒露) | October 8 | Cold dew |

| Sōkō (霜降) | October 23 | Frost descent |

| Rittō (立冬) | November 7 | Beginning of winter |

| Shōsetsu (小雪) | November 22 | Small snow |

| Taisetsu (大雪) | December 7 | |

| Tōji (冬至) | December 22 | Winter solstice, middle of winter |

| Shōkan (小寒) | January 5 Small Cold | a.k.a. 寒の入り (Kan no iri) entrance of the cold |

| Daikan (大寒) | January 20 | Major cold |

Days can vary by approximately a day.

Zassetsu

| January 17 | 冬の土用 | Fuyu no doyō | |

| February 3 | Setsubun | The eve of Risshun by one definition. | |

| March 21 | 春社日 | Haru shanichi. Also known as 春社 (Harusha, Shunsha). | |

| March 18 - March 24 | 春彼岸 | Haru higan (seven days surrounding Shunbun) | |

| April 17 | 春の土用 | Haru no doyō | |

| May 2 | 八十八夜 | Hachijū hachiya (meaning 88 nights - since Risshun). | |

| June 11 | 入梅 | Nyūbai (meaning entering tsuyu_ | |

| July 2 | 半夏生 | Hangeshō | |

| July 15 | 中元 | Chūgen (Sometimes considered a Zassetsu) | |

| July 20 | 夏の土用 | Natsu no doyō | |

| September 1 | 二百十日 | Nihyaku tōka (meaning 210 days) | |

| September 11 | 二百二十日 | Nihyaku hatsuka (meaning 220 days) | |

| September 20 - September 26 | 秋彼岸 | Aki higan | |

| September 22 | 秋社日 | Aki shanichi Also known as 秋社 (Akisha, Shūsha). | |

| October 20 | 秋の土用 | Aki no doyō |

hanichi days can vary as much as about 5 days. Chūgen has a fixed day. All other days can vary by approximately one day.

Many zassetsu days occur on multiple seasons

- Setsubun (節分) refers to the day before each season, or the eves of Risshun, Rikka, Rishū, and Rittō; especially the eve of Risshun

- Doyō (土用) refers to the 18 days before each season, especially the one before fall which is known as the hottest period of a year.

- Higan (彼岸) is the seven middle days of spring and autumn, with Shunbun at the middle of the seven days for spring, Shūbun for fall.

- Shanichi (社日) is the Tsuchinoe (戊) day closest to Shunbun (middle of spring) or Shūbun (middle of fall), which can be as much as -5 to +4 days away from Shunbun/Shūbun.

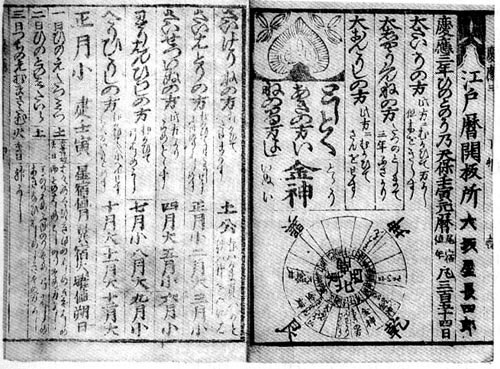

Rokuyō

The rokuyō (六曜) are a series of six days that supposedly predict whether there will be good or bad fortune during that day. The rokuyō are still commonly found on Japanese calendars and are often used to plan weddings and funerals, though most people ignore them in ordinary life. The rokuyō are also known as the rokki (六輝).

- 先勝 Senshō Good luck before noon, bad luck after noon. Good day for beginnings (in the morning).

- 友引 Tomobiki Bad things will happen to your friends. Funerals avoided on this day (tomo = friend, biki = pull, thus a funeral might pull friends toward the deceased). Typically crematoriums are closed this day.

- 先負 Senbu Bad luck before noon, good luck after noon.

- 仏滅 Butsumetsu Symbolizes the day Buddha died. Considered the most unlucky day. Weddings are best avoided. Some Shinto shrines close their offices on this day.

- 大安 Taian The most lucky day. Good day for weddings and events like shop openings.

- 赤口 Shakkō The hour of the horse (11 am - 1 pm) is lucky. The rest is bad luck.

The rokuyō days are easily calculated from the Japanese Lunisolar calendar. Lunisolar January 1 is always senshō, with the days following in the order given above until the end of the month. Thus, January 2 is tomobiki, January 3 is senbu, and so on. Lunisolar February 1st restarts the sequence at tomobiki. Lunisolar March 1st restarts at senbu, and so on for each month. The last six months repeat the patterns of the first six, so July 1 = senshō, December 1st is shakkō and the moon-viewing day of "August 15th" is always a "butsumetsu." This system did not become popular in Japan until the end of the Edo period.

April 1

The first day of April has broad significance in Japan. It marks the beginning of the government's fiscal year.[2] Many corporations follow suit. In addition, corporations often form or merge on that date. In recent years, municipalities have preferred it for mergers. On this date, many new employees begin their jobs, and it is the start of many real-estate leases. The school year begins on April 1. (For more see also academic term)