The Zoroastrian calendar is a religious calendar used by members of the Zoroastrian faith, and it is an approximation of the (tropical) solar calendar. To this day, Zoroastrians, irrespective of geographic location, adhere to (variations of) this calendar for religious purposes.

History

Prior to the calendar reform Sassanid emperor Ardashir I (226–241 CE), the calendar in common use since at least the mid-5th century BCE had a 360-day year, and was based systemically on the Babylonian calendar. Under that system, the Kabiseh (lack) that accumulated over time was leveled out by the periodic intercalation of a thirteenth month, as determined by observation. The tradition of naming the days and months after divinities was based on a similar Egyptian custom, and had been previously instituted at some point between 458 and 330 BCE, very probably during the reign of Artaxerxes II (404–358 BCE).

The calendar introduced by Ardashir I had a 365-day year based even more closely on the Egyptian calendar. It still had 12 months of 30 days each, and the months and days of the month that had been named in Achaemenid times remained as they were. However, the 12th month was followed by five additional Gatha or Gah days, after the ancient Avesta hymns of the same name. In addition, all forms of intercalation were discarded, and the first day of the religious year was shifted from the 1st day of the 1st month to the 1st day of the 9th month.

The new system created confusion and was met with resistance, and many Zoroastrian feasts and celebrations had two dates, a tradition that is maintained by some Zoroastrians to this day. Many rites were practiced over many days instead of one day and duplication of observances was continued to make sure no holy days were missed.

The situation got so complicated that another calendar reform was implemented by Ardashir's grandson Hormizd I (272–273 CE). The new and old holy days were linked together to form continual six-day feasts. Norouz (or Navroz), the first day of spring, was an exception: the first and the sixth day of the month were celebrated as different occasions and the sixth day became more significant as Zoroasters’ birthday rather than as a continuation of the spring festival celebrations.

Since the reforms of Ardashir I also did away with all forms of intercalation, the calendar and seasons had diverged by four months by the time Yazdegerd III (632–651 CE) ascended the throne. This resulted in the Gahambars (the seasonal festivals) being celebrated at the wrong times of the year. Yazdegerd III had another reform prepared, but it was not implemented when the Arabs overthrew dynasty.

Yazdegerdi Era

Following Alexander's conquest of Persia in 330 BCE, the Seleucids (312-248 BCE) instituted the Hellenic practice of dating by era, as opposed to dating by the reign of individual kings, and began the era of Alexander (now referred to as the Seleucid era). This practice was not considered acceptable to the Zoroastrian priests, who consequently founded a new era, the era of Zoroaster—which incidentally led to the first serious attempt to establish a historical date for the prophet. The Parthians (150 BCE–224 CE), who succeeded the Seleucids, continued the Seleucid/Hellenic tradition, and it was not until the calendar reform of Ardashir I that dating by regnal year was reinstituted.

The Zoroastrian calendar uses the Y.Z. suffix for its calendar era (year numbering system), indicating the number of years since the coronation in 632 CE of Yezdegerd III, the last monarch of the Sassanian dynasty.

Variations

As a result of the lack of intercalation embodied in the calendar reforms of Ardashir I, the calendar and the seasons were, over time, no longer synchronized. Already in the 9th century, the Zoroastrian theologian Zadspram had noted that the state of affairs was less than optimal and estimated that at the time of Final Judgement the two systems would be out of sync by four years.

In 1006, the roaming New Year's day once again coincided with the day of the vernal equinox, and (according to legend) it was resolved that the Zoroastrian calendar henceforth intercalate an additional month every 120 years as prescribed in Denkard III.419 (it must however be noted that the Denkard is itself a 9th century work). At some point between 1125 and 1250, the Parsi-Zoroastrians of the Indian subcontinent inserted such an embolismic month, named Aspandarmad vahizak (the month of Aspandarmad but with a vahizak suffix). That month would also be the last month intercalated: subsequent generations of Parsis neglected to insert a thirteenth month.

At the time of the decision to intercalate every 120 years, the calendar was called the Shahenshahi (imperial) calendar. The Parsis, not aware that they were not intercalating correctly, continued to call their calendar Shahenshahi. This practice has survived to this day, and adherents of other variants of the Zoroastrian calendar denigrate the Shahenshahi as "royalist".

Meanwhile, the Zoroastrians who remained in Iran never once intercalated a thirteenth month. Around 1720, an Irani-Zoroastrian priest named Jamasp Peshotan Velati travelled from Iran to India. Upon his arrival, he discovered that there was a difference of a month between the Parsi calendar and his own calendar. Velati brought this discrepancy to the attention of the priests of Surat, but no consensus as to which calendar was correct was reached. Around 1740, some influential priests argued that since their visitor had been from the ancient 'homeland', his version of the calendar must be correct, and their own must be wrong. On June 6, 1745, a number of Parsis in and around Surat adjusted their calendars according to the recommendation of their priests. This calendar became known as the Kadimi calendar in both India and Iran, which in due course became contracted to Kadmi or Quadmi.

In 1906, Khurshedji Cama, a Bombay Parsi, founded the "Zarthosti Fasili Sal Mandal", or Zoroastrian Seasonal-Year Society. The Fasili or Fasli calendar, as it became known, was based on an older model, introduced in 1079 during the reign of the Seljuk Malik Shah and which had been well received in agrarian communities.This calendar had two salient points: 1) It was in harmony with the seasons and New Year's day coincided with vernal equinox. 2) It followed the Egyptian-Zoroastrian model (12 months of 30 days each plus 5 extra days), but also had an auto-regulatory leap day every four years: the leap day, called Avardad-sal-Gah, followed the five existing Gah days at the end of the year. The Fasli society also claimed that their calendar was an accurate religious calendar, as opposed to the other two calendars, which they asserted were only political.

The new calendar received little support from the Indian Zoroastrian community since it was considered to contradict the injunctions expressed in the Denkard (III.419). In Iran, however, the Fasli calendar gained momentum following a campaign in 1930 to persuade the Iranian Zoroastrians to adopt the new calendar of the seasons, which they called the Bastani calendar. In 1925, the Iranian Parliament had introduced a new Iranian calendar, which (independent of the Fasli movement) incorporated both points proposed by the Fasili Society, and since the Iranian national calendar had also retained the Zoroastrian names of the months, it was not a big step to integrate the two. The Bastani calendar was duly accepted by the majority of the Zoroastrians. In Yazd, however, the Zoroastrian community resisted, and to this day follow the Kadmi calendar.

In 1992, all three calendars happened to have the first day of a month on the same day, and although many Zoroastrians suggested a consolidation of the calendars, no consensus could be reached. Some priests also objected on the grounds that the religious implements would require re-consecration, at not insignificant expense.

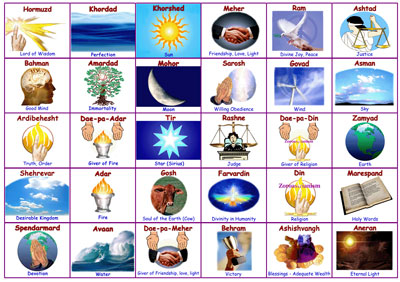

Month and day names

The months and the days of the month in the Zoroastrian calendar are dedicated to, and named after, a divinity or divine concept. The religious importance of the calendar dedications is very significant. Not only does it establish the hierarchy of the major divinities, it ensures the frequent invocation of their names since the divinities of both day and month are mentioned at every Zoroastrian act of worship.

The oldest (though not dateable) testimony for the existence of the day dedications comes from Yasna 16, a section of the Yasna liturgy that is—for the most part—a veneration to the 30 divinities with day-name dedications. In those Avestan language verses, the names appear in the following sequence:

- Dadvah Ahura Mazdā

- Vohu Manah

- Aša Vahišta

- Khšathra Vairya

- Spenta Ārmaiti

- Haurvatāt

- Ameretāt

- Dadvah Ahura Mazdā

- Ātar

- Āpō

- Hvar

- Māh

- Tištrya

- Geuš Urvan

- Dadvah Ahura Mazdā

- Mithra

- Sraoša

- Rašnu

- Fravašayō

- Verethragna

- Rāman

- Vāta

- Dadvah Ahura Mazdā

- Daēna

- Aši

- Arštāt

- Asmān

- Zam

- Manthra Spenta

- Anaghra Raočā.

The quarternary dedication to Ahura Mazda was perhaps a compromise between orthodox and heterodox factions, with the 8th, 15th and 23rd day of the calendar perhaps originally having been dedicated to Apam Napat, Haoma, and Dahmān Afrīn respectively. The dedication to the Ahuric Apam Napat would almost certainly have been an issue for devotees of Aredvi Sura Anahita, whose shrine cult was enormously popular between the 4th c. BCE and the 3rd c. CE and who is (accretions included) a functional equal of Apam Napat. To this day these three divinities are considered 'extra-calenary' divinites inasfar as they invoked together with the other 27, so making a list of 30 discrete entities. Faravahar, believed to be a depiction of a Fravashi (guardian spirit), to which the month and day of Farvardin is dedicated

The 2nd through 7th days are dedicated to the Amesha Spentas, the six 'divine sparks' through whom all subsequent creation was accomplished, and who—in present-day Zoroastrianism—are the archangels.

Days 9 through 13 are dedications to Yazatas of the five Nyashes of the Khordeh Avesta: Fire, Water, Sun, Moon, the star Tištrya that here perhaps represents the firmament in its entirety. Day 14 is dedicated to the soul of the Ox, linked with and representing all animal creation.

Day 16, leading the second half of the days of the month, is dedicated to the divinity of oath, Great Mithra (like Apam Napat of the Ahuric triad). He is followed by those closest to him, Sraoša and Rašnu, likewise judges of the soul; the representatives of which, the Fravashi(s), come next. Verethragna, Rāman, Vāta are respectively the hypostases of victory, the breath of life, and the (other) divinity of the wind and 'space'.

The last group represent the more 'abstract' divinities: Religion, Recompense, and Justice; Heaven and Earth; Sacred Invocation and Endless Light.

In present-day use, the day and month names are the middle Persian equivalents of the divine names or the concepts, but in some cases reflect Semitic influences (for instance Tištrya appears as Tir, which Boyce (1982:31-33) asserts is derived from Nabu-*Tiri). Moreover, the names of the 8th, 15th, and 23rd day of the month—reflecting Babylonian practice of dividing the month into four periods—can today be distinguished from one another: These three days are respectively named Dae-pa Adar, Dae-pa Mehr, and Dae-pa Din, middle Persian expressions meaning 'Creator of' Atar, Mithra, and Daena respectively.

The divinities to which month-names are dedicated are twelve of the thirty to whom days of the month dedicated, but the month-name dedications additionally establish which of the twelve divinities were/are considered to rank higher than the others. The list of month-names does not occur anywhere in the texts of the Avesta, but are known from commentaries and translations of those texts, from various regional Zoroastrian calendars of the Sassanid era and from living usage. In addition to Dae (middle Persian for Avestan Daena) and thus a dedication to Ahura Mazda and six dedications to the Amesha Spentas, the remaining five are considered to be the most significant of the Yazatas: Farvadin (Avestan: Fravashi), Tir (Tishtrya), Mehr (Mithra), Aban (Apo), and Adar (Atar).

There is some evidence that suggests that in ancient practice Dae, and not Fravardin, was the first month of the year. In a 9th century text, Zoroaster's age at the time of his death is stated to have been 77 years and 40 days (Zadspram 23.9), but this age cannot be verified unless Dae was the first month of the year. It is also worth noting that Pateti, the day of introspection, is on the first day of the month of Fravardin—which, as New Year's day, is a day of celebration.